People prayed with extended arms to represent a cross (Origen, “Hom. in Exod.”, iii, 3, Tertullian, “de Orat.”, 14). So also to make the sign of the cross over a person or thing became the usual gesture of blessing, consecrating, exorcising (Lactantius, Divine Institutes IV:27), actual material crosses adorned the vessels used in the Liturgy, a cross was brought in procession and placed on the altar during Mass. The First Roman Ordo (sixth century) alludes to the cross-bearers (cruces portantes) in a procession.

As soon as people began to represent scenes from the Passion they naturally included the chief event, and so we have the earliest pictures and carvings of the Crucifixion. The first mentions of crucifixes are in the sixth century. A traveller in the reign of Justinian notices one he saw in a church at Gaza in the West, Venantius Fortunatus saw a palla embroidered with a picture of the Crucifixion at Tours, and Gregory of Tours refers to a crucifix at Narbonne. For a long time Christ on the cross was always represented alive.

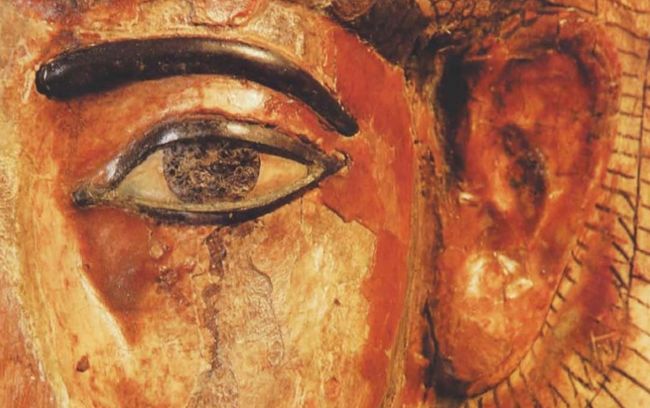

A Syriac manuscript

The oldest crucifixes known are those on the wooden doors of St. Sabina at Rome and an ivory carving in the British Museum. Both are of the fifth century. A Syriac manuscript of the sixth century contains a miniature representing the scene of the crucifixion. There are other such representations down to the seventh century, after which it becomes the usualcustom to add the figure of our Lord to crosses; the crucifix is in possession everywhere.

The conclusion then is that the principle of adorning chapels and churches with pictures dates from the very earliest Christian times: centuries before the Iconoclast troubles they were in use throughout Christendom.

So also all the old Christian Churches in East and West use holy pictures constantly. The only difference is that even before Iconoclasm there was in the East a certain prejudice against solid statues. This has been accentuated since the time of the Iconoclast heresy (see below, section 5). But there are traces of it before; it is shared by the old schismatical (Nestorian and Monophysite Churches that broke away long before Iconoclasm. The principle in the East was not universally accepted.

The emperors set up their statues at Constantinople without blame; statues of religious purpose existed in the East before the eighth century (see for instance the marble Good Shepherds from Thrace, Athens, and Sparta, the Madonna and Child from Saloniki, but they are much rarer than in the West. Images in the East were generally flat; paintings, mosaics, bas-reliefs. The most zealous Eastern defenders of the holy icons seem to have felt that, however justifiable such flat representations may be, there is something about a solid statue that makes it suspiciously like an idol.

Read More about The Falcon part 3