A sober contemporary of that family, the businessman Dioscoros from the modest city of Aphrodito (Aphrodite’s town, back when the landscape was given Greek names), left a trove of documents that reveal prosperous provinciality far up the Nile. From him we have leases and loans, receipts and wills, petitions and depositions—a whole range of documentation that once pervaded the Roman empire but that has all but disappeared, leaving us with only a fragmentary sense of the way this meticulous, busi¬nesslike world worked. Thanks to Dioscoros, we know that a donkey sold for a little more than half a year’s earnings for a farmer, making it the ideal capital investment (and much cheaper than a boat). It would eat about two percent of its load of wheat in a day and carry that wheat twenty-five miles or more. This is the scale at which a camel was an expensive purchase, reserved only for long-haul shipments by the rich, and horses and mules were for government officials and soldiers. Most of the Mediterranean world lived among donkeys.

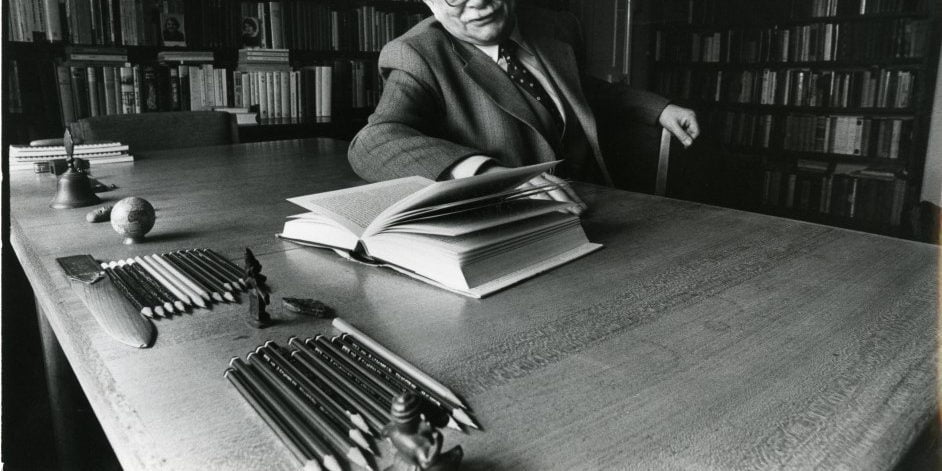

Dioscoros’s modern biographer

Dioscoros’s modern biographer compares him to a Japanese minor court poet or a Chinese official. But that runs the risk of encouraging us to look down on him. To see a man like Dioscoros whole, you need to see him from below, from the village perspective in which he appeared as a great man. Dioscoros dazzled that audience by combining a good head for business and book learning (from a good education in Alexandria) and also by writing poems:

I always want to dance. I always want to play the lyre.

I strike up my lyre to praise the solemn festival with my words.

The Bacchae have cast a spell on me Within the Arab community.

That traditionalist Dioscoros who wrote of the Bacchae surely attended Christian services regularly. When he was in Alexandria he could have attended the church of the Evangelists, later dedicated to saints Cyrus and John. This was originally the temple of Isis and Manetho, hastily con¬verted for Christian use in 391 when sacrifice was banned. (Curiously enough, the cures that occurred thanks to the protection of the old gods continued under the new management.)

Dioscoros was a minor figure

Now, Dioscoros was a minor figure compared with the members of the Apion family. Based in Oxyrhynchus (“sharp-nosed,” from a fish found there) on the middle Nile 100 miles south of Cairo, the Apiones were local landlords and—during the sixth century—grandees of imperial stature. The wealthy daughter of the murdered philosopher Boethius went into exile at Constantinople and found it advantageous to marry one of her own daughters into the Apion dynasty. One Apion was the praetorian prefect (roughly equivalent to a prime minister) for the east under the emperor Anastasius, but it was Flavius Apion II who dominated his part of Egypt as few others had done since the time of the pharaohs. He served Justinian at court and as a general, before spending most of his career from the 550 s to the 570s doing what ancient gentlemen did best: controlling his home turf. His family owned 75,000 acres of precious, river-watered land in his home district and maintained an extensive private staff that practically amounted to a government. The people who lived under this dominion were sharecroppers at best, and might have been forgiven for thinking they were virtual slaves on their own land.